Here on Cape Cod we have two distinct types of kettle ponds. Herring-fed and landlocked. At Woods Hole’s Marine Biological Laboratory as part of the SES program, I set out this past fall to investigate mercury levels in these two different systems and found two things. One, mercury levels are very high in certain species of fish. Two, herring-fed ponds tend to be significantly lower in mercury.

The rest of this article contains unpublished data and is merely a student project where I am presenting my findings. For more extensive research, contact the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

More...

Mercury Poisoning: What You Need To Know

Back in 2019 American Radio personality Howard Stern and his doctors thought he was dying of cancer. He was about to get treated with chemotherapy because his white blood cell count was very low when he got a phone call from Dr. Agus. He told Stern that he should get tested for mercury, as Stern had been eating lots of seafood recently. He may have saved his life (or his precious hair anyways) as it turns out that Howard Stern had mercury poisoning.

American radio personality, Howard Stern.

Mercury exists in many forms, but only the form of methylmercury is toxic. This form is generated in the bottom sediment of ponds and lakes, from which it is taken up by organisms and ultimately consumed by fish. And aside from lowering white blood cell count, methylmercury can cause a “loss of peripheral vision, muscle weakness, and impairment of hearing, speech, thinking, and walking" according to the US EPA.

Unfortunately for us fish eaters, Massachusetts has extremely high mercury levels in ponds to the extent that the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH) has set eating restrictions and recommendations on 289 local ponds, due to very high levels of mercury (MA DPH).

A consumption warning sign at Grew's Pond in Falmouth from the DPH due to high mercury levels.

Herring-Fed vs. Landlocked Ponds

When looking at all the Cape Cod ponds tested by the DPH, I found something intriguing...the ponds that were herring-fed tended to have lower mercury levels.

Here on Cape Cod, herring-fed ponds have river outflows that drain into the ocean. For thousands of years, sea-run herring have utilized these rivers as a means of transportation. Every spring these herring come in from the ocean, and lay their eggs in the ponds.

Importantly, herring have historically low levels of mercury compared to other fish. Was it possible that the herring were entering the ponds and lowering the mercury levels in bass, trout, and perch?

I knew that herring were in the herring-fed ponds, but were the fish actually eating them? And how was this affecting the mercury levels?

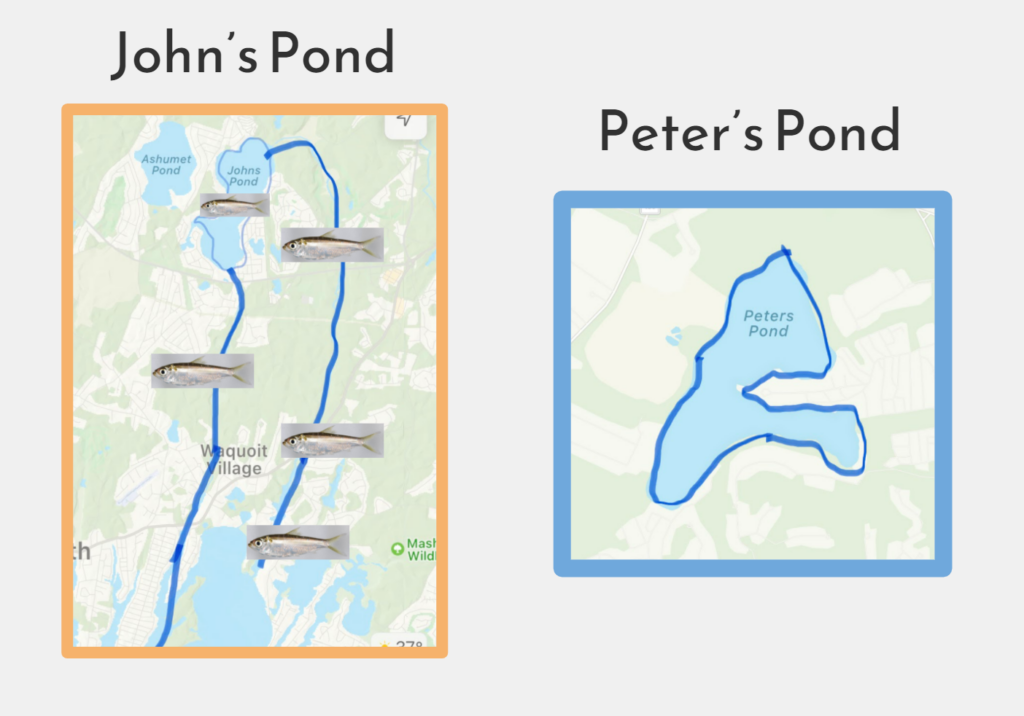

Johns Pond (left) is a herring-fed pond that receives an annual dose of herring from the ocean. Peter’s Pond (right) is landlocked and does not contain herring.

What The Fish Are Eating

We can use chemistry to approximate what each fish is actually eating in a given pond. Because quite literally "you are what you eat," we can analyze the molecules in fish tissue samples to guess what they are eating with something called stable isotopes.

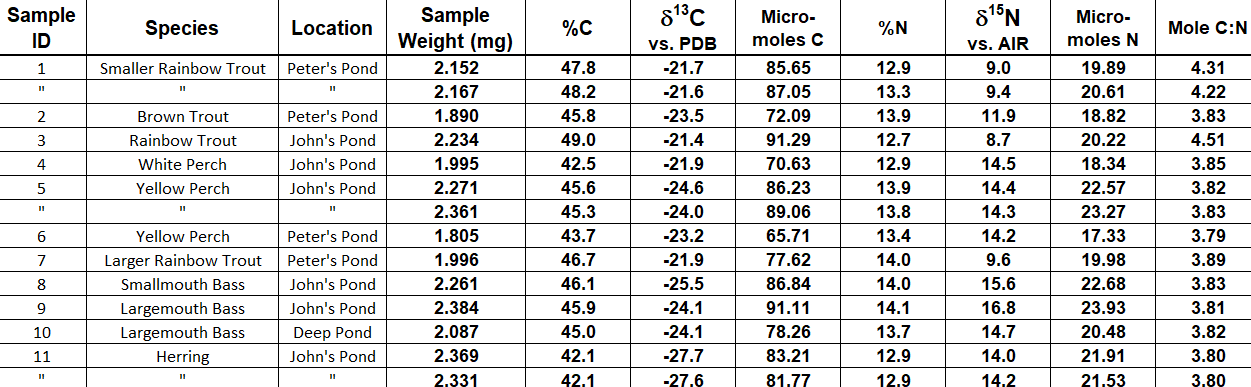

This is an example of what raw stable isotope data looks like:

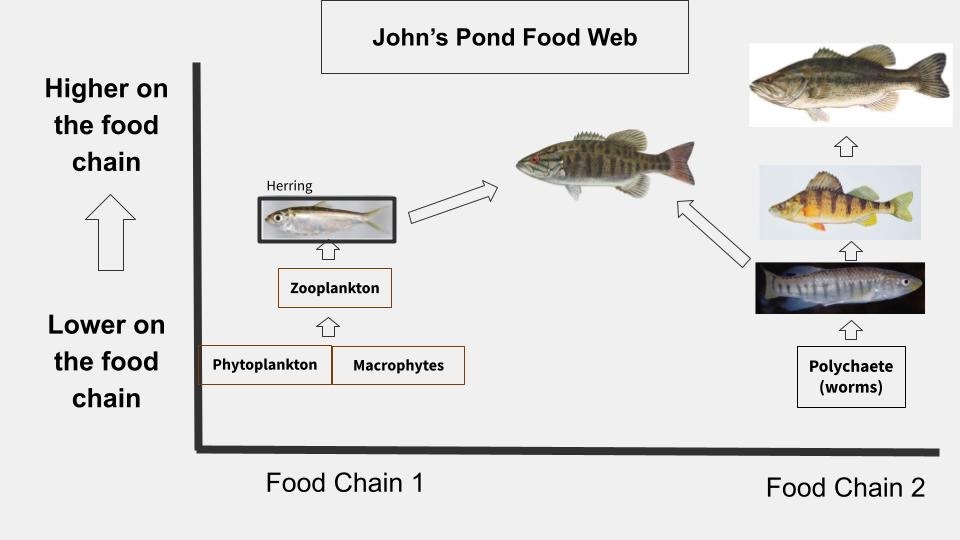

You can take that raw data and craft what the food web looks like:

A simplified version of what the food web looks like in John's Pond based on our data (In reality it is much more complex).

Based on this, we found good evidence that the herring were in fact making their way into the diet of the fish in the pond and were getting eaten primarily by smallmouth bass. That's not to say other fish aren't eating herring, but we found that smallmouth are eating the most herring out of any other fish.

Interestingly, of all the fish we tested during this project, the smallmouth bass were the only fish to actually spit up herring when we captured them!

In terms of trout, we observed brown trout to be much more fish-eating than rainbow trout, which tended to eat more flies and worms. And the larger the individual, generally the more fish-eating they became.

Mercury Levels on Cape Cod

The US FDA recommends that no individual should consume fish over a concentration of 0.46 ppm (parts per million) mercury. And the US FDA also prohibits the selling of any fish greater than 1 ppm mercury. At or above this level, known as the Action Level, it is illegal to sell fish at any capacity.

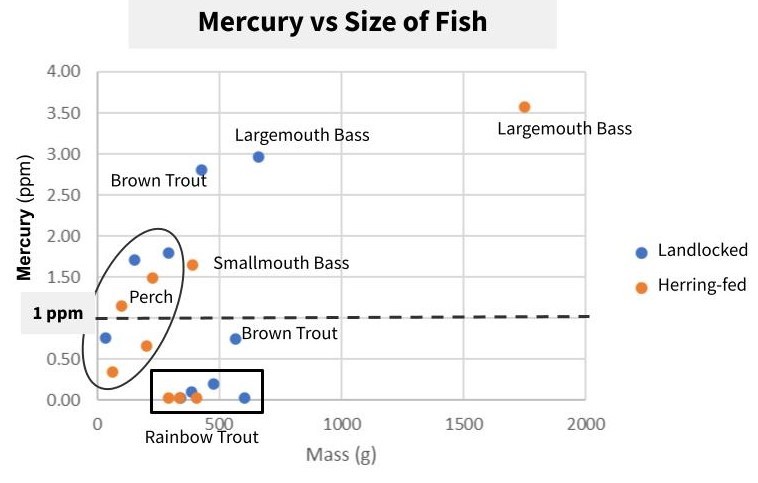

Besides rainbow trout, all fish had individuals that were above the FDA’s maximum threshold (1 ppm), and are not only recommended to avoid eating, but would be illegal to sell due to high mercury levels.

A graph of our fish samples, where the higher up on the graph, the higher the mercury concentration. Not only do some of these fish approach the 1 ppm mark, but they far exceed it.

With perch (both yellow and white), roughly half of our samples were above the FDA maximum threshold for mercury.

Fish Consumption Recommendations

Having eaten fish personally from the kettle ponds my entire life, I found this alarming. However, I did not find it surprising. Our numbers were consistent with other studies and testing of mercury in these ponds.

According to our data, rainbow trout had consistently the lowest levels of mercury out of any other fish.

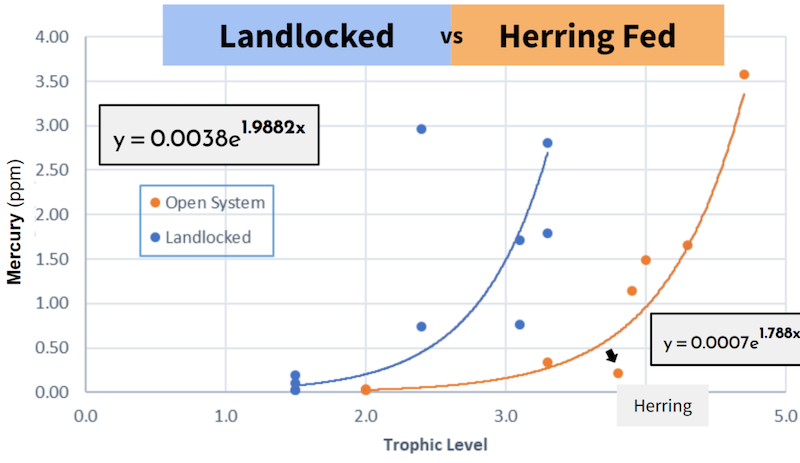

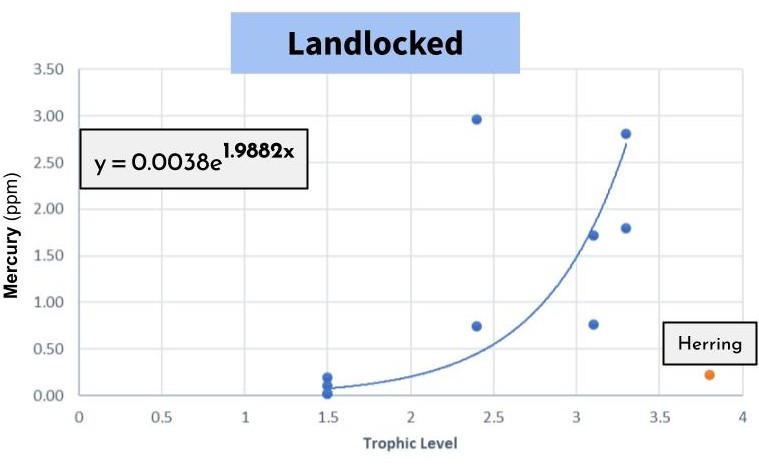

Below is a graph that compares trophic level (how high up something is on the food chain) and mercury levels. What's interesting when we compare the two, is that the landlocked pond increases at a faster rate than the herring-fed pond in mercury! This is partly due to the location of herring on the graph, which sits very low due to its low level of mercury.

If herring were introduced to Peter's Pond, it’s hard to imagine that they wouldn’t bring the mercury levels down.

We observed a 21.9% faster bioaccumulation rate of mercury in the landlocked pond. Which means that not only does the mercury accumulate in the fish tissue more readily, the fish generally have higher levels of mercury in the landlocked pond.

However, herring is not the only factor at play here. We observed higher mercury in the plankton, plants, and flies before we got to herring on the food chain. So it's quite likely that the outflow from the river is affecting the the water chemistry and thus the mercury levels, but that's a question for another day.

What we can conclude from this project however, is that if you are concerned about consuming mercury, perhaps eating from a herring-fed pond, or

eating rainbow trout as an alternative to other species may minimize your risk.

If you want to learn more about this project, you can watch my 15-minute talk on it here.

Thanks!

Nick Beltramini

Acknowledgements: Thanks to the Marine Biological Lab for providing me with the resources to undertake this project. Thank you Inke Forbrich for mentoring me throughout, and Daniel Obrist at UMass Lowell for allowing me to utilize your lab to run samples. Also thank you to the following people involved who I could not have done this project without: Jade Fiorilla, Tin Wang, Marshall Otter, and Marcus Mekhail.

This article contains unpublished data and is merely a student project where I am presenting my findings. For more extensive research, contact the MA DPH.

Is it possible to introduce a chemicle or feed that would leach mercury out of biomass? It seems that women that are pregnant should avoid eating any fish caught from the kettle ponds.

Interesting idea…I’m no expert chemist, but if I had to guess I’m sure it’s possible to remove Mercury from the fish tissue with technology. I would assume that it would be incredibly expensive, and would requiring you killing the fish, and probably destroying the meat in the process however (pulverizing/vaporizing).

Yes, I think to minimize risk that would be smart for pregnant women

Hi Ryan, have any studies been done that show how fast the mercury enters the fish tissue? Most trout that I have fished for are stocked. Do we know if the trout are safe to consume? That you for sharing this information.

Hi Bernie,

I talked to the biologists at the Sandwich Trout Hatchery last year who stock many of the ponds in Southeast MA and the Cape. They told me that the trout have very little mercury when they are stocked. This is probably due to their pellet diet, which contains practically no mercury. Unfortunately the DPH does not include trout in their mercury analyses, and your question was one of the major questions I wanted to answer with this project. We unfortunately did not acquire enough trout to make any conclusions of the rate of mercury accumulation once trout are stocked.

BUT…generally the longer any fish is in the pond, the larger it grows, and the more mercury it will acquire. And there are studies that document this in other fish with size vs mercury.

Here’s one on Massachusetts bass and yellow perch.

https://www.mass.gov/doc/freshwater-fish-mercury-concentrations-in-a-regionally-high-mercury-deposition-area-december/download

(Figure 4 is the graph of size vs mercury concentration)

Nick,

Thank you and keep up the wonderful work.

Thanks for the post Nick! I’m also curious about the source of the mercury, and what can we do to help improve the situation? I suppose continuing to restore herring runs is a great place to start.

Perhaps! This would be a good argument to do so. Over the past couple of decades the input of mercury into the atmosphere has been slowly declining over time, so hopefully we’re on the right track.

Good to know, thanks for the follow up comment Nick!

Good work Nick!

I occasionally keep a trout to eat and feel better now knowing that the rainbow trout I ate had a better chance to have lower mercury levels.

Just curious about the source of the mercury. I had always thought that emissions from coal burning power plants were the source. Does your research present a different, naturally occurring source?

Hi Ken,

That’s right! It’s well documented that the burning of fossil fuels, primarily coal, is the largest contributor to mercury into the atmosphere. It’s crazy to me that a coal plant hundreds of miles away can lead to mercury in Cape Cod. There are also a variety of natural sources as well (volcanic eruptions, forest fires, etc) that can contribute.

That being said, there are also multiple garbage incinerators in MA, which also produce mercury and might contribute. There’s studies from the DPH that show that the ponds closest to these incinerators are very high in mercury compared to ponds further away.

Exactly how much and where exactly the mercury comes from I don’t know, and our research didn’t suggest it. But if I had to guess it would probably be very difficult to find out.